Provenance

Nowadays Rembrandt’s paintings can be admired in many parts of the world. Having been made in the Northern Netherlands, they have found their way to various countries and continents, while passing through different hands. Aside from portraits, which can be assumed were commissioned by the sitter or a relative, little is known about the first owners of Rembrandt’s paintings. In only in a few cases can their provenance be traced back to the artist’s studio.

left: Rembrandt, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, dated 1653, canvas, 143.5 x 136.5 cm, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

right: Rembrandt, Homer, dated 1663, canvas, 107 x 82 cm, The Hague, Mauritshuis

One of the most well-documented commissions is that of the Sicilian art collector Antonio Ruffo who ordered three paintings from Rembrandt in the middle of the 17th century. The commission of these three paintings and their travel to Italy has been documented in letters, notes and inventories. In September of 1654, a note was written in a supplement to the 1648 inventory of Ruffo’s collection. This note mentions a three-quarter length figure of a philosopher, made in Amsterdam by a painter called Rembrandt. This philosopher has been identified as the painting Aristotle with a Bust of Homer in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Signed by Rembrandt in 1653, it took less than a year for this painting to arrive in Sicily.

In July of 1661 an invoice directed to Ruffo was drawn up for the costs of two other paintings by Rembrandt, an Alexander the Great and a Homer. The latter has been identified as the Homer currently kept at the Mauritshuis; the former is generally assumed to be lost. After the completion of the Alexander, Rembrandt and Ruffo had a dispute about the quality of the canvas of the painting, which has been recorded in a few documents. Eventually the dispute was settled, and the Alexander was added to the inventory of Ruffo’s collection on November 20th, 1662. Around the same time, the Homer was sent back to Amsterdam for completion, to return to Messina 2 years later, where it was hung together with the other two Rembrandts among paintings by Italian masters.

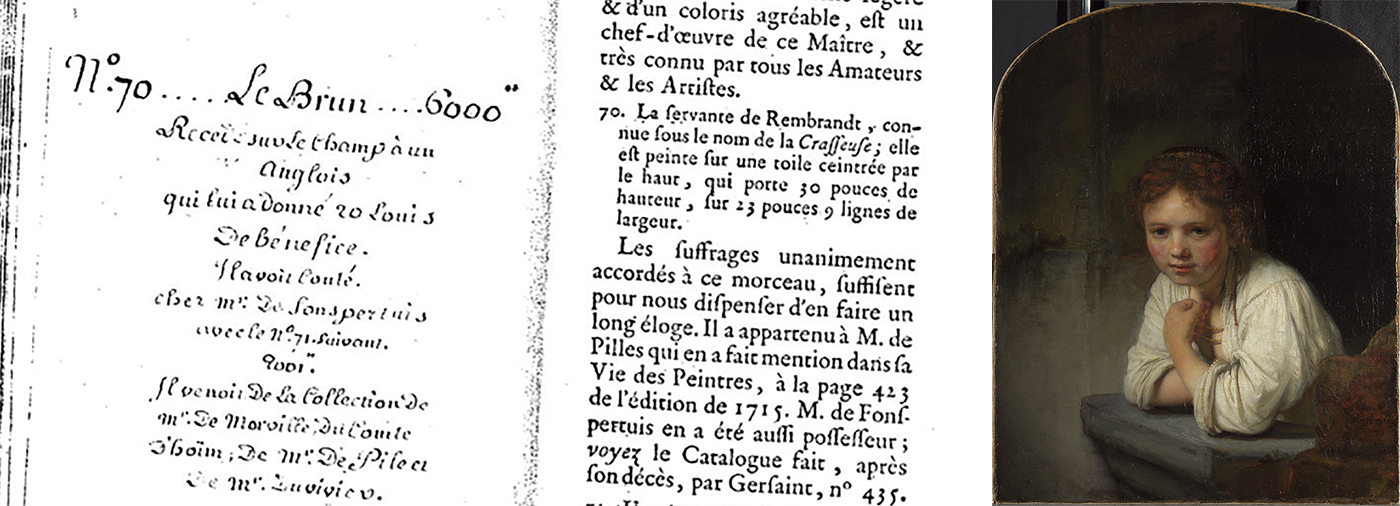

left: Auction Catalogue Remy, 1776-12-10 / 1777-01-22, lot.no. 70 (Lugt no. 2616); annotation in a copy of this catalogue (RKD, The Hague)

right: Rembrandt, Girl at a Window, dated 1645, canvas, 81.6 x 66 cm, London, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Aside from archival sources, publications can also provide key information on the whereabouts of a painting. For instance, auction catalogues often hold information on the provenance of a painting. Auction catalogues frequently mention the seller of the painting, and sometimes also refer to its earlier provenance. Many copies of the sale catalogues also contain annotations - handwritten notes by the owners of the catalogues – which mention the price for which the painting was sold and frequently also the name of the (assumed) buyer.

According to an annotation in a copy of a sale catalogue, Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window was bought by the art dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun at an auction in Paris of December 10th, 1776. The annotation also reports that after he purchased the painting, Le Brun sold it to an Englishman, making 20 pieces of silver as a profit.

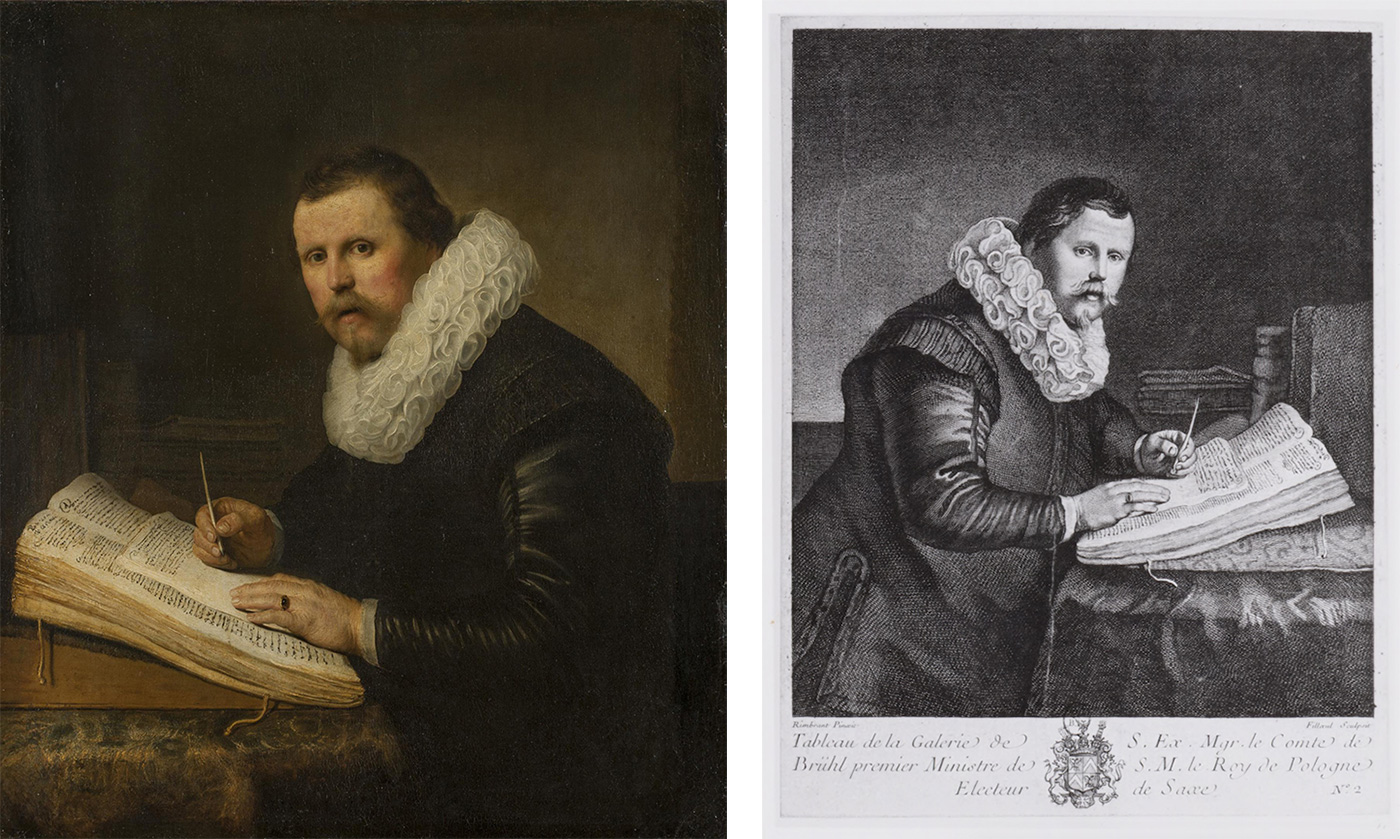

left: Rembrandt, Portrait of a Man at a Writing Desk, dated 1631, canvas, 104.4 x 91.8 cm, Saint Petersburg, Hermitage

right: Pierre Filloeul after Rembrandt, Portrait of a Man at a Writing Desk, published in 1754, 275 x 218 mm, Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale de France

Beside written sources, images such as reproduction prints can also hold information on a paintings’ whereabouts. Art collectors often commissioned reproduction prints to be made after key works in their collection, in order to enhance its renown. In 1754 Heinrich von Brühl published the Recueil d’estampes gravéez d’après les tableaux de la Galerie er du Cabinet de S.E. Mr. le Comte de Brühl, a collection with reproduction prints after paintings in his art collection, among which a couple of Rembrandt paintings. These prints were made by various artists, including Pierre Filloeul, who made an engraving after Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Man at a Writing Desk, currently in the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. Because of this it is known that this painting was part of Van Brühl’s collection from 1754.

left: Rembrandt, Portrait of Johannes Wttenbogaert, dated 1633, canvas, 130.5 x 104.5 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

center and right: Normal light studies: photograph, overall (backside), and details backside, 2009, Carola van Wijk

A painting itself sometimes also holds evidence of previous owners. The reverse of a painting can contain seals, labels, inscriptions or inventory numbers that might be useful when searching for its former whereabouts.

Wax seals and a label on the stretcher of Rembrandt’s Portrait of Johannes Wttenbogaert indicate that the painting had been part of the collection of the Conte Girolamo Manfrin in Venice.

left: Possibly Rembrandt and studio or Studio of Rembrandt, Tronie of an Old Man, c. 1630, panel, 46.9 x 38.8 cm, The Hague, Mauritshuis

right: normal light studies: slide, overall (backside), 1999, Ed Brandon

The incomplete label on the reverse of the Tronie of an Old Man in the Mauritshuis is proof that it had once been in the hands of the art dealer Durand-Ruel et Cie in Paris.

The backside of a painting can also hold other evidence. When the Second World War broke out, multiple Dutch museums undertook preparations for the possible evacuation of important art works. To this end, an ordering system was added to the reverse of a group of paintings. In the case of the Rijksmuseum, by April 1939 red, white and blue dots had been added to paintings that were considered irreplaceable, difficult to replace, or replaceable respectively. At the Mauritshuis they applied the same coloring system, but instead of circles they used triangles.

left: normal light studies: slide, overall (backside), 1996, Jorgen Wadum, Petria Noble; Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, dated 1632, canvas, 169.5 x 216.5 cm, The Hague, Mauritshuis

right: normal light studies: photograph, 2008, Frans Pegt; Rembrandt, The Denial of St. Peter, canvas, 154 x 169 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Further reading:

- J. Giltaij, Ruffo en Rembrandt : over een Siciliaanse verzamelaar in de zeventiende eeuw die drie schilderijen bij Rembrandt bestelde, Zutphen 1999

- S.E. Ekelund and E.E. van Duijn. 2017, “Red, white or blue – An evacuation priority marking system on paintings in Dutch museums and its applicability in conservation and research today”, in: ICOM-CC 18th Triennial Conference Preprints, Copenhagen, 4–8 September 2017, ed. J. Bridgland, art. 1903. Paris: International Council of Museums.